-

The Early Years (1965-1971)

by Emery Olcott and Orren TenchSturrup Nuclear

In 1965, Emery Olcott and Chuck Greer, who had been undergraduates together at Yale University and later received MBAs at The MIT Sloan School, found themselves working in New York City. Chuck was employed by McKinsey and Company and Emery was working for Bell Telephone. By this time they had been out of school for about three years and, although they had good jobs and young families, they both had entrepreneurial instincts and thirsted for the opportunity to break away from these large corporations which provided security but little in the way of excitement.

Back then the Wall Street Journal included an obscure advertising section where one could place small inexpensive ads for business opportunities. It was here that they found a small-print, three-line ad for a company engaged in electronics, specifically nuclear electronics or nucleonics. Neither of them knew anything about nucleonics and little about electronics for that matter but they were intrigued by the ad, and since the company was located in Middletown, Connecticut they decided to make the two-hour trip up the Merritt Parkway to check it out.

This was during the heyday of the Nuclear Power build-up in the US and anything having to do with nuclear sounded pretty exciting. Of course, this was before nuclear power plants began to spend heavily on instrumentation for radiochemistry and health physics. The real market for nucleonics was in education and in nuclear physics research at both universities and at national laboratories.

Emery and Chuck made their way to 50 Silver Street in Middletown where they were met by the two partners who owned the business, called Sturrup, Larrabee, and Warmers at the time. The business was basically an electronics job shop which historically had done contract manufacturing for a variety of local firms. Somewhere along the line the company had become involved in making marine electronics, but this part of the business was virtually defunct even if their assets were mostly made up of obsolete inventory associated with this business. The other part of the business was called Sturrup Nuclear which had its genesis in manufacturing electronics for Yale University which needed instrumentation for their extensive nuclear research program centered on their Tandem Van-de-Graff (Heavy Ion Accelerator). Charlie Gingell headed up the design team at the Heavy Ion Accelerator and he and his team provided designs to Sturrup which turned out the hardware. Eventually Sturrup gained the right to sell this electronics to other universities and research centers around the country. This was before the advent of the Nuclear Instrumentation Module (NIM) and, at that time, there were probably a half dozen or so different modular electronics designs in use around the US, with no physical or electrical compatibility between any of them. This was about to change because researchers, led by Lou Costrell at NBS (later NIST), had conceived a new national standard for modular nucleonics which they dubbed the NIM Standard. It was obvious that all the companies involved in the business would have to retool or face extinction. Faced with this imperative the owners of Sturrup decided to bail, hence the ad in the WSJ.

If Emery and Chuck didn’t already know this, they soon would. Meanwhile their meeting with the owners continued over lunch where one of them got drunk and the other went to sleep. At the end of the day Emery and Chuck figured that, just by staying sober and awake, they could do a far better job managing the company and maybe even turn it around. In any case the price was attractive, about $35,000 lock, stock and barrel.

The Name

Although $35,000 is not much money today it was a substantial sum in 1965 for two young guys not long out school, so Chuck and Emery took in some investors including some former classmates, relatives, and Chuck’s dentist, to mention only a few, none of whom would become active partners in the venture. Some of them got together, however, to come up with a new name for the company. They wanted to avoid a strictly technical name which might not serve them through diversification into disparate businesses, should that occur. Eventually they got around to place names and then to world capitals. The choice came down to Canberra Industries or Pretoria Industries and they chose the former. In retrospect we can agree that this early decision was a good one!

The Assets

Besides the obsolete marine inventory there was some inventory of the modular nucleonics which was losing value quickly as the NIM Standard took over. In the first year of operation Emery visited existing customers and unloaded some of this equipment which customers needed to complement what they already had in use. After all, the customers would eventually have to switch over to NIM as well.

Personnel and Organization

Although Sturrup clearly had the capability to manufacture designs provided by others, they had no bona fide engineers on staff. It was believed that they desperately needed help from Charlie Gingell to provide design help and Chuck and Emery set about to get it. For some unknown reason Charlie was not happy that Sturrup had been sold, so they knew they would have to make a compelling offer. In fact they offered him 10% ownership in Canberra at no cost if he would only continue to cooperate with Canberra. He turned them down flat and spent the next 20 years trying to justify that decision by blackballing Canberra products at Yale, during which time we sold absolutely nothing there. It didn’t help much that we vigorously protested a NIM order they gave to ORTEC in the early days. We learned several more times that it is dangerous to protest an award, especially so by going over the head of the user or decision maker.

Sturrup did have an experienced technician on staff, an Englishman named Henry Webb who had worked on radar for the British during WW-II. He carried the title Chief Engineer but he had no proven design experience. Having no other viable option, Chuck and Emery set Henry to work designing new NIM Instruments and to their surprise and delight he turned out to be a prolific genius at analog design. Soon Henry was turning out new instruments at a record pace. During that time the IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium was the showcase for new products from all the nuclear instrument companies, and Henry would work feverishly to have some new instruments available for that exhibition. Many were the times we would arrive at the factory to find Henry, stripped down to his skivvies, finishing an overnighter. The production ladies got a kick out of Henry’s antics and encouraged this behavior.

In 1966, Les Daniels, who had worked with Orren Tench at Hamilton Standard (UTC), joined Canberra, becoming the second design engineer in the organization. About a year later, Canberra needed someone to manage the Engineering Department, and Orren took that position.

Manufacturing was headed up by Carl Sluzarczyk who ruled that organization with an iron hand. It became known as the Holy Roman Empire during the many years that Carl was in charge. The manufacturing staff included a good number of attractive young ladies, most of whom were named Debbie it seems in retrospect, and good times were enjoyed by all. The newly hired Engineering Manager (Orren) was interviewing a candidate for a secretarial position one afternoon after hours, when a commotion erupted just outside his open-plan office. The candidate, Ann-Marie Mucimeci, watched in horror as Carl walked past pushing a wheeled trash barrel with Carol Pearson’s legs sticking out and flailing about. Carol, head down in the barrel, was laughing and screaming like a maniac. Quiet young Ann-Marie took the job after all!

With a young and spirited staff under a lot of pressure it is not surprising that many ways were found to let off steam. The annual anniversary party in July became one such outlet and the Christmas party at a local watering hole, The Coach and Four, was another. These were employee only functions for many years.

“Mooning” in the most unusual circumstances was a favorite. Once, in a convoy on the Mass Pike, someone pulled one off from the driver’s side window. We still do not know who or how. The last may have been at a joint Canberra-Packard sales meeting in Florida when the entire (last place “Olympic”) team mooned the assembled audience.

At a trade show (IEEE?) in New York, the Canberra team was having dinner at Mama Leoni’s Restaurant. The conversation turned to streaking, a current fad, and money started accumulating on the table with the understanding that anyone could claim it by running sans pants to the NY Hilton, several blocks away. The pot got up to about $175 when Sam Knoll grabbed it and headed for the door. The others followed him at a distance, witnessing people from the sidewalk and from shops drawn into the wake.

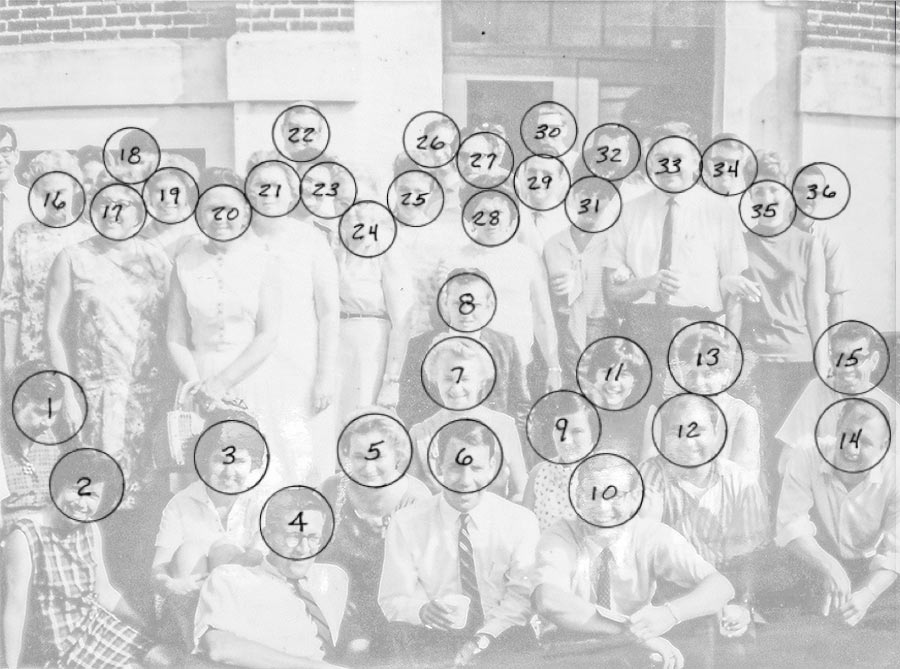

Below is a photo of the Canberra Staff circa 1968. It was taken at the time of the Anniversary Party. Click here for a key to the personnel. Alas, we have not been able to identify everyone.

See key for identifying people below

See key for identifying people below

1) Ada Via

2) ?

3) ?

4) Emery Olcott

5) ?

6) Dave Smith

7) ?

8) ?

9) ?

10) Chuck Greer

11) Stockroom Clerk (married Tom Perzan)

12) Steve Sackter

13) Barbara Jennings (Rigdon)

14) ?

15) Orren Tench

16) Doris Price

17) ?

18) Les Daniels19) ?

20) ?

21) ?

22) Rick Pederson

23) Bernice Russo

24) Betty Weatherill

25) ?

26) Bob Margadonna

27) Henry Webb

28) ?

29) Al Hoelck

30) ?

31) Debbie ? (Stockroom Clerk)

32) ?

33) Carl Slusarczyk

34) Sam knoll

35) Carol Pearson

36) Chuck RisleyProducts

ORTEC was a relatively mature established company when Canberra started. Their NIM Line carried model numbers in the 400 series. Canberra’s strategy was to offer the same or better performance for an equal or lesser price. To make it easy for customers to compare products, Canberra chose, with some impertinence, to use model numbers in the 1400 series. Thus, while ORTEC’s top amplifier was the Model 410, the Canberra equivalent was the Model 1410. By and large the Canberra instruments performed well against the competition, and the variety and quantity of the Canberra NIM grew quickly. ORTEC had a relatively large engineering staff by that time and they were quick to disparage Canberra engineering. They probably thought that we could not survive with so few resources. In fact they could probably have forced Canberra into bankruptcy had they used all their resources against us, but they probably thought we would fail on our own.

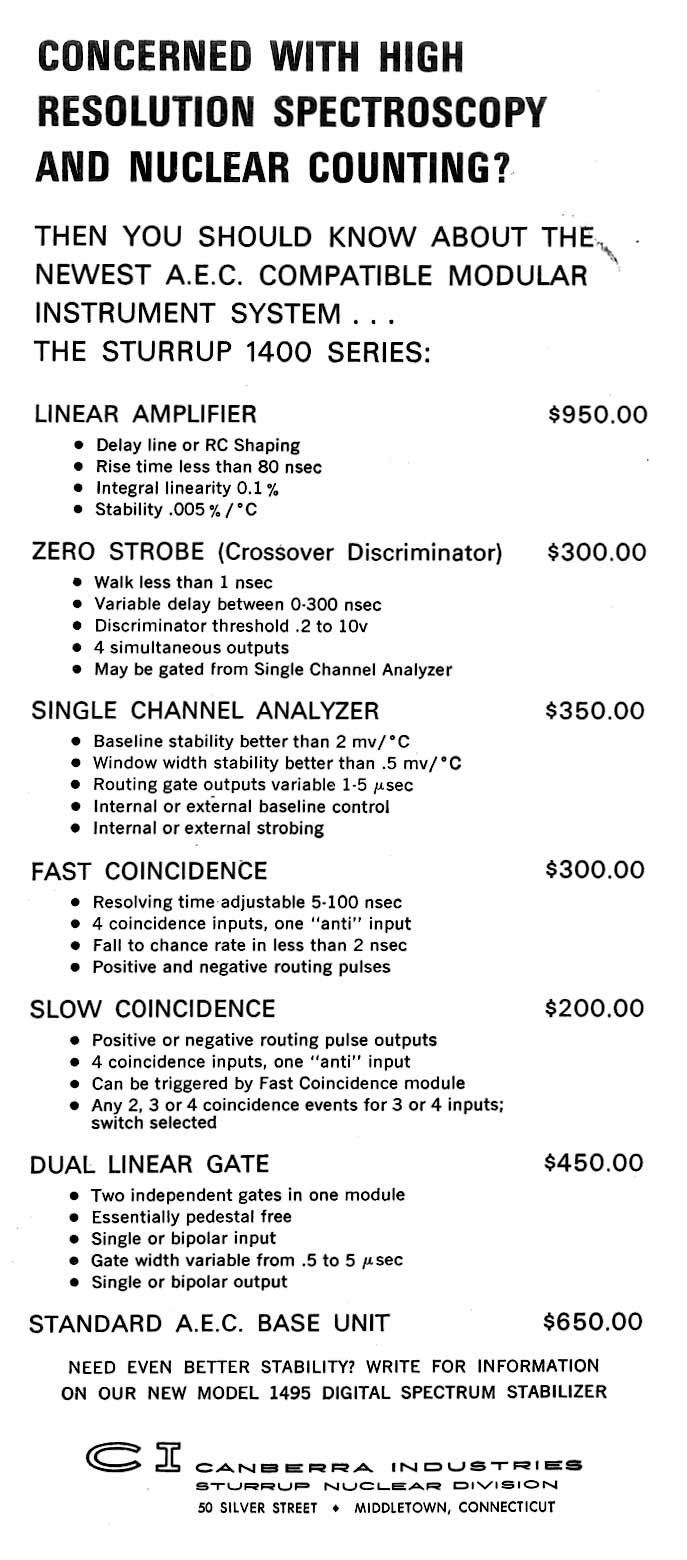

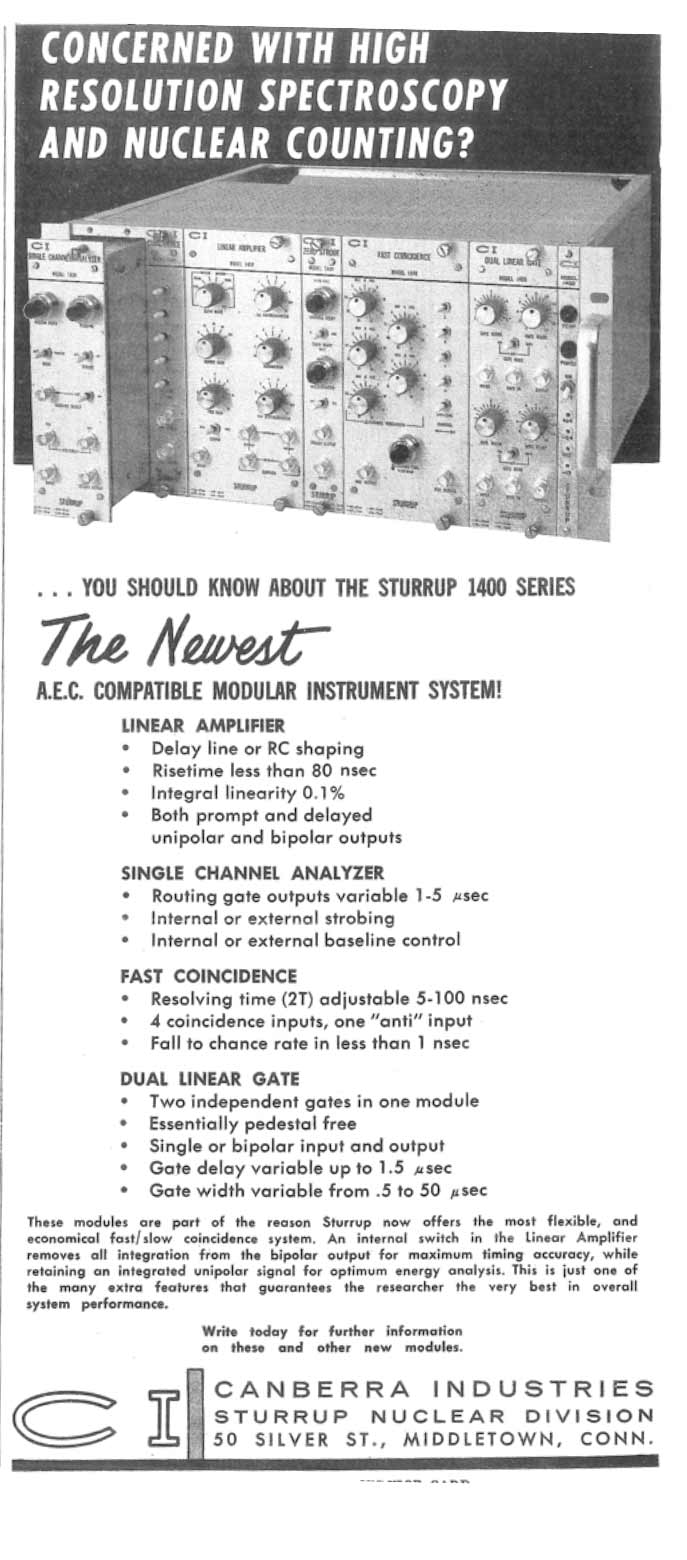

Below you will find two of the earliest advertisements Canberra published. The first came out in the December 1965 Issue of Nucleonics, a trade journal that ceased publication in 1967. The second came out in the same magazine in January 1966, with pictures of some of the first NIMs.

Note that the name Sturrup was still being used for the instruments business.

Sales Organization

Emery took responsibility for sales and hired local manufacturer’s representative firms to sell the products around the US and to a lesser extent abroad. It was not easy to find good reps who were not already allied with competitors like ORTEC and Tennelec, but he did hire some good ones including Jim Johnson in the Midwest and Gene Embry in the mid-atlantic states. Gene later moved to Meriden and became our Domestic Sales Manager for a year or two. Ed Zieba in Canada, who founded APTEC, became an early representative there. David Smith came up from New York, and with help from Canberra, set up a rep organization called Amplitudes, Inc., which handled New England. Dave would eventually head up the Canberra’s clinical laboratory business.

Facilities

Sturrup occupied the upper floor of an ancient mill building in Middletown. A machine shop was located on the bottom floor. There was no AC except for window units in the “executive suite”. The upper floor had oiled plank floors which became very slippery and nasty from spilled beer during the annual anniversary party (employees only). The indefatigable John Rak, who spoke little English, did all the maintenance on the facility including office construction using rough plywood and 2X4s, painting everything in the dark blue and light grey official Canberra colors. He also packed all the instruments for shipment on a daily basis.

When we ran out of space on the upper floor the machine shop moved out and we took over the first floor which was occupied first by the Engineering Department joined later by the Detector Division and the Automation Division (Data NIM).

When the first floor was under re-construction Orren called the local Sherwin-Williams store and the manager came over with paint samples which he applied to a wall so we could choose a color. Chuck saw what was going on and called Orren to his office demanding to know “what the hell is that guy doing with the paintbrush?” Chuck made it clear in no uncertain terms that office colors were fixed in two-tone blue for all time. Properly admonished, Orren caved but told Chuck that the Engineering Department would be disappointed with the over-rule. Hours later Chuck called Orren and told him “paint it any damn color you want”. Thus ended the tradition of matching office and instrument colors at Canberra.

Around 1970 we needed more space and an informal search led us to the Dominel Press building on Gracey Avenue in Meriden. Dominel Press printed comic books on several huge printing presses. Although the presses were gone by the time we bought the place, virtually every surface was covered with thick layers of chaff and dust produced in the cutting process of comic book production. We bought this two-story building which gave us room to grow even if we continued to rent a substantial portion of it to an auto parts wholesale business. Eventually we took over the entire building. Here we resided through the first financial crisis and for several years thereafter.

The Division Manager Program

By 1968, seemingly flush with their success in growing the NIM business, Emery and Chuck set about to broaden the Canberra product line. Recognizing what they themselves had achieved in growing Canberra and recognizing the difficulty in growing vertically from a base organization focused on the existing business, they conceived a plan to grow somewhat horizontally by establishing “divisions” each manned by a partnership comprising a Technical Director and a General Manager. The principals in these divisions would be able to earn equity in them if successful and eventually convert this equity into Canberra stock.

For potential General Managers, Emery and Chuck turned to business schools and for a few years, they hired some of the top MBA graduates from great schools like Harvard, MIT and Stanford. These new hires were assigned to sales territories around the country (to learn something about real business and about sales). By and large they replaced the manufacturer’s representatives throughout the US. While in this role they had the opportunity to look for new businesses or product lines that would be attractive investments for Canberra. Among these recruits were Sam Knoll, George Hodgetts, Rick Pederson, Tom Moir, Jack Wilson, and Steve Johnson, all of whom served as regional salesmen for a year or more.

The Technical Directors would be recruited from diverse sources. It was expected that they would come with technical expertise or with product concepts ready for development. At about this time, the Wall Street Journal published a story about Canberra in which Chuck and Emery described their vision of growing the company through the Division Manager program. This spawned inquiries from lots of people who were fascinated by the opportunity to become entrepreneurs within Canberra, including people who worked for competitors. Dick McKernan, who was working for the Norden Division of United Aircraft (now UTC) at the time, was attracted by that WSJ article and he joined the company as a potential Division Manager and was sent to Chicago to cover sales in the mid-west.

Over the next two or three years several divisions were established and others were in an embryonic state. They included:

Detector Division- Ge(Li) Detectors

The Technical Director was Dr. Hans Fiedler who came from Nuclear Diodes. Orren Tench became General Manager. He was chosen for this position perhaps to demonstrate that these division opportunities were open to existing employees as well as to outsiders. Largely because of the knowhow and hard work of Fiedler, this division became quite profitable and the principals were rewarded appropriately.

Data Systems Division- Automation

The Technical Director was Gerry Matthews who came from Hamner Electronics. Rick Pederson, who sold for us in California, was the General Manager. After flirting with all manner of automation challenges, X-Ray Diffraction became the target application. A large (25,000) installed base of GE XRD-5 Diffractometers was the carrot. A substantial number of instruments were developed and sold with the DataNIM name. Divisions were allowed to choose unique paint colors and Data Systems chose dark maroon for some reason. Ed Fisher, who designed many of them, irreverently dubbed them “red devils” and collectively as “purple s..t”. This division never became very profitable but it gave Canberra exposure outside the nuclear instruments field.

One notable benefit evolved from Data Systems. It happens that they sold a system to The Ford Motor Company Research Center. At that time Ford was actively looking for investment opportunities in small innovative companies, and Canberra, because of the DataNIM sale to Ford Research, came to the attention of the guy who had responsibility for identifying and evaluating opportunities. He eventually made his way to Meriden and came back often eventually getting Ford to invest two million dollars (in two installments) in Canberra “Preferred” stock, which didn’t exist, of course, but was created solely for Ford. It is not for us to speculate as to why Canberra was chosen for this investment. Let us just say that our receptionist at that time was a captivating young woman who was especially friendly toward visitors from out of town. In any case this preferred stock sale gave Canberra a shot of much needed cash at a good time. The stock was retired under very favorable terms a few years later.

So if DataNIM never became a highly profitable product line it did make a significant contribution after all.

Medical Products Division - Portable Defibrillators, Infant Hearing Tester, Emergency Radio- Communication

The Technical Director was Les Hammer who came from Hamilton Standard. Another engineer joined with his idea for an infant hearing tester. Sam Knoll, who was originally slated as Fiedler’s partner, chose this opportunity instead. The defibrillator never sold in quantity, the hearing tester never sold at all, and the radio-communication system sold to some degree but it could not support the division.

Clinical Laboratory Division

The Technical Director was Hervey Weitzman, a pathologist. Dave Smith became General Manager. This opportunity was spawned by the advent of automated blood analyzers introduced by Technicon. Many small laboratories could not afford the $200k, so Canberra was able to buy them up and consolidate the business. Canberra Clinical Laboratories became the largest medical laboratory in Connecticut if not New England, but not before the irrepressible Ed Fisher penned this unforgettable slogan for the laboratory: “Feces and urine are our bread and butter”.

Credit Card Protection Service

It never went further than one desk drawer, but Dave Smith sold protection plans to individuals before the Clinical Lab opportunity came along. At that time individuals could be held (partially) responsible for misuse of credit cards, and companies sprang up offering to notify creditors of lost or stolen cards for individuals who paid a fee for protection. The barrier to entry into the business was non-existent, and Smith signed up a handful of customers with absolutely no system in place to provide the service. Within days a subscriber left a phone message saying she had lost her purse containing several cards. Dave frantically searched through the database (make that drawer) but could not find the woman’s information. The next morning she called back to say that the purse had been found. Dave assured her that he would be able to re-validate her cards without interruption. Both breathed a big sigh of relief.

Computer Peripherals

This business never made the transition to division status, but Steve Johnson and Les Daniels developed a triple-cassette computer storage device, the model 2020, which was used for years in Canberra systems. They faced a major challenge in finding a cassette transport (mechanics) befitting a high end digital recorder and traveled all over the country looking for the best available. Incredibly, the best by far was made by Raymond Engineering, which was located just a few miles up I-91 from Meriden.

Software

Canberra took over a struggling software development company, Agrippa Ord , with three employees; a manager, Jim Francis, plus two programmers, Gene Sengstock and Steve Piner. The manager didn’t last past the first financial crisis, but Gene went on to become a very productive and resourceful Product Manager for various product lines at Canberra. Steve, a dedicated programmer, continued in this role for many years. When computer memory was at a real premium they developed an operating system, Canberra Laboratory Automation Software System (CLASS) which required a mere 6-8 kilobytes of memory from the DEC PDP-11 minicomputer that was used by Canberra in its early computer-based systems.

The MCA Business

Background

By and large the companies that made NIMs did not make Multi-channel Analyzers (MCAs) in the early days and vice versa. Established MCA manufacturers included Packard Instruments, Nuclear Data, Northern Scientific, Hewlett Packard, and Technical Measurements Corporation (TMC) which was located in Connecticut not far from Canberra. MCA technology was much more complex than that of the typical NIM instrument and required far more engineering effort and expertise than resided in most of the companies making NIMs. TMC was probably for some time the most successful MCA manufacturer. Their management team sought growth by recklessly broadening the product line, and around 1968 they found themselves in bankruptcy. It didn’t help that they spent heavily on perks including not one but two corporate airplanes.

Canberra realized that this presented an excellent opportunity to hire some of their key people to develop an MCA product line, and some discussion took place between Canberra management and TMC professionals. For whatever reason, agreement wasn’t reached and the key engineers went to work for a company called Geoscience. Harvey Roberts was the MCA guru and Walt McKay, who lived in Texas, was their very technically competent sales manager. Under Geoscience they developed several good MCAs, but the competition was stiff and they eventually failed. As always it took more than a “better mousetrap” to ensure success.

For very little money Canberra was able to buy the MCA product line from Geoscience and thereby lured Harvey Roberts and his team to join the company. Harvey was brilliant at digital design and he led the team for the next twenty+ years that made Canberra number one among MCA manufacturers. It is for good reason that we recognize Harvey as the “Father of the Canberra MCA”.

The MCA design team was only a part of the inheritance Canberra received from the demise of TMC. Gene DellaVecchia came to Canberra starting in sales in New England and, after a hiatus, went on to play an active role in Packard Instruments after it was acquired many years later. Bobby Maggi also worked in sales for several years in the New York territory.

But most importantly our late associate and boon companion, Ben Campagnuolo, came to Canberra in a sales support role. Ben eventually took charge of the worldwide sales force, instilling into it the alacrity and responsiveness that helped propel the company into a leading position in virtually all the markets it served.

The First Financial Crisis and Reorganization

By 1971 it was becoming clear that the myriad divisions, most of which had not turned the corner financially, were draining the life from Canberra. Chuck had calculated that an investment of 37 cents was needed for every dollar of increased sales. Even if the calculation was done on the back of an envelope like many of his others, it was probably not far off. Our bank, Hartford National, probably realized that we were on a downward spiral and they reneged on our revolving credit line, leaving the company in dire straits.

Chuck resisted cutting back operations to right the ship. He organized a frantic effort to increase sales by sending our factory specialists to woo customers but this didn’t work. Finally the Board, spurred on by Ford, asked for Chuck’s resignation and appointed Emery, who seemed to be much more pragmatic in dealing with this crisis, as President.

Emery did what had to be done to save the company. Division products that had legs were consolidated into the base business. Others were discontinued. Division independence came to an end. Hans Fiedler, who believed the company was doomed, left the Detector Division and moved to his homeland, Germany, where he set about to make Ge(Li) detectors under the name GETAC. Orren was left to run the detector operation, which was adrift in process and hardware problems, with only one able assistant, Marie Darin. Somehow they pulled it off, and the Detector Division survived in name and in operations, but not as a financial entity.

Steve Johnson became the national sales manager, replacing Gene Embry. Dick McKernan, who the company had planned to send to England to run the sales organization there, came to Meriden instead and took over the Engineering Department, replacing Don Grosso, who had replaced Orren in that job. Sam Knoll became CFO replacing Jim Stamm, who went to work for his father-in-law in the pants business, denying Emery his supply of the garish garb he wore from time to time at company functions. George Lake, who Canberra had recruited from ORTEC, became Operations Manager for a while, but left after a failed plot to convince the Board to name him President. Most of the other would-be division managers left the company at around this time.

Setting the stage for the future.

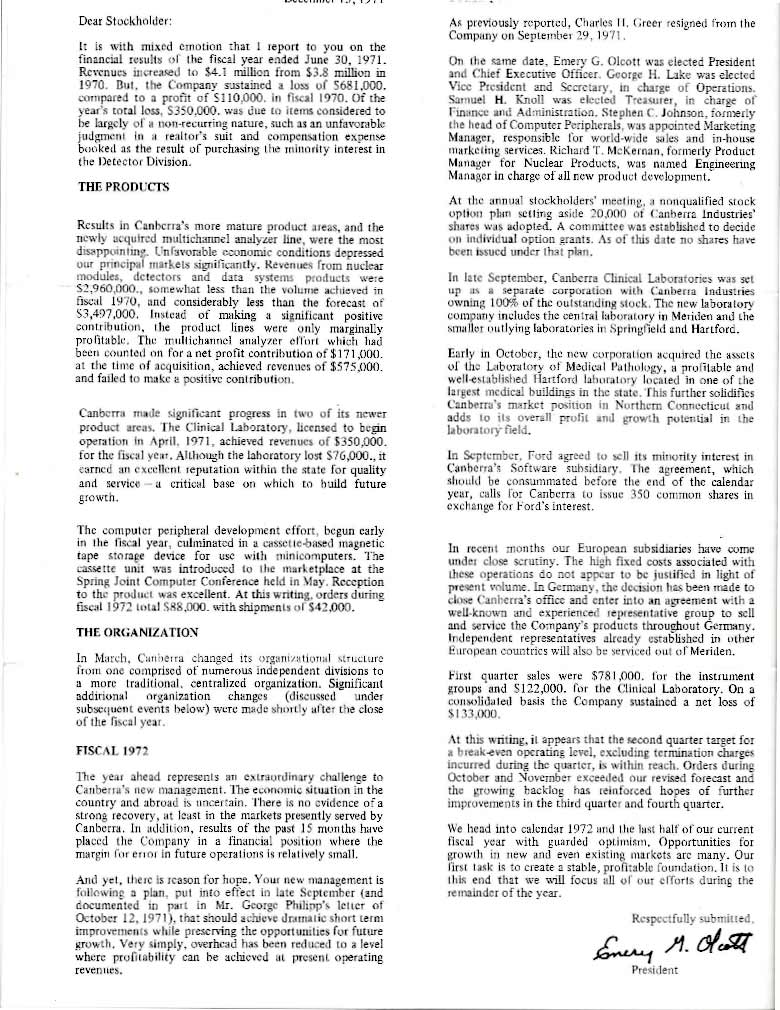

The following letter to stockholders, dated December 15, 1971, more-or-less sums up the condition of the company shortly after Emery took over as President and CEO.

After the re-organization and the end of the Division Manager program, Canberra was left with three instrument product lines: NIMs, Detectors, and MCAs, and with a growing clinical laboratory business. Subsequent installments will deal with the instruments business. The clinical laboratory business, while an important asset and indeed the financial savior of the company in a later crisis, is not part of this story going forward.